El mejor lugar para cobertura de noticias y cultura latina en Chicago. | The place for coverage of Latino news and culture in Chicago.

¿Cómo sonaba exactamente la Navidad del pasado?

Gracias a un erudito musical del área de Chicago con talento para desenterrar el pasado, el público local será el primero en siglos en escuchar una serie de villancicos antiguos que se remontan al México y Guatemala de los siglos XVI y XVII.

El grupo detrás del proyecto es el Newberry Consort, que interpreta música antigua utilizando instrumentos y técnicas de la época. El Consort organiza sus conciertos anuales de “Navidad latinoamericana” del 13 al 15 de diciembre, que culminan con una matiné en el Museo Nacional de Arte Mexicano en Pilsen.

El programa de este año presenta algo único: la “columna vertebral”, en palabras de la directora Liza Malamut, son nueve piezas estudiadas y editadas por Paul Gustav Feller-Simmons, estudiante de doctorado en la Universidad Northwestern.

Cuatro de las obras fueron escritas e interpretadas en un convento en Puebla, México, entre 1630 y 1740 y ahora residen en el Centro Nacional de Investigación, Documentación e Información Musical (CENIDIM) en la Ciudad de México.

Las otras cinco fueron “descubiertas” en un cofre en las tierras altas de Guatemala y son aún más antiguas, ya que datan de entre 1562 y 1635. Esos manuscritos ahora se conservan en la Universidad de Indiana.

Con ocho instrumentistas y seis cantantes, las actuaciones de este fin de semana marcarán la primera vez que se interpreta esta música desde que las obras fueron redescubiertas y catalogadas por académicos en la década de 1960. Además, estos villancicos antiguos pronto estarán disponibles para cualquiera que quiera interpretarlos; Feller-Simmons publicará una antología de esta música y más en 2025.

“Paul ha transcrito todos estos a notación moderna. Le estamos muy, muy agradecidos por ponerlos a nuestra disposición”, dijo Malamut.

La forma en que estos villancicos se reintrodujeron en el catálogo festivo actual es una historia de erudición, paciencia y arqueología musical moderna, del tipo que practica Feller-Simmons, de 35 años de edad.

El Newberry Consort presentará una hermosa aproximación de lo que uno podría haber escuchado hace 400 años en los villancicos navideños recientemente descubiertos. | Cortesía Newberry Consort

The digging started back when he was an undergraduate student in Chile, assisting musicologist Alejandro Vera in his recovery of a rare manuscript by Santiago de Murcia, a renowned composer of Baroque guitar music. In recent years, he’s worked with another scholar, Cesar Favila, on a project documenting the centuries-old music of Latin American nuns.

Ultimately, Feller-Simmons’ research was a great fit for the Newberry Consort, which wanted to broaden the concept of its annual “Mexican Christmas” concerts to encompass more historical sounds of Latin America.

Just like travel in those days, it took some time for musical fads to cross the Atlantic. The music of colonial Spain tended to be old-fashioned compared to what was happening in mainland Europe. Even the earliest pieces on the Newberry Consort’s program, from the 1560s or so, contain music more akin to that composed in 1510.

“It would be like listening to swing today,” Feller-Simmons said.

Some of the music is signed by composers or copyists, while other pieces are anonymous. But the manuscripts offer up clues that Feller-Simmons has worked to decode.

For example, some of the Old Spanish inscriptions in the Guatemalan manuscripts contained enough unusual misspellings and syntax errors that he suspected their copyists were non-native speakers — quite likely some of the countless Indigenous Americans who converted under duress by Spanish missionaries. Other songs in the collection were written in the Mayan languages spoken in the region.

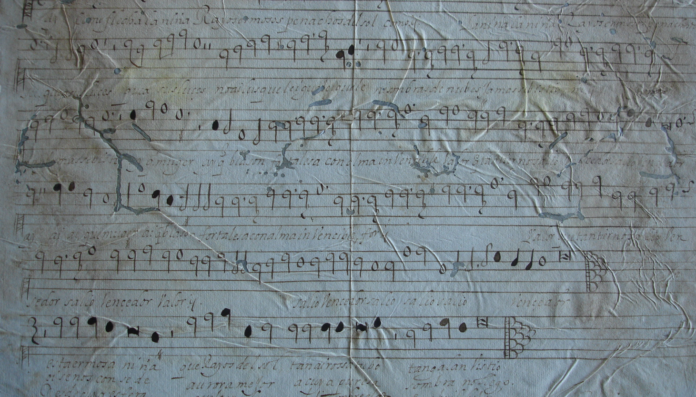

Algunos de los manuscritos fueron descubiertos en un cofre en las tierras altas de Guatemala que datan entre 1562 y 1635. | Cortesía Paul Gustav Feller-Simmons/Lilly Library, Indiana University Bloomington

Names also appeared in the Puebla manuscripts — of women, most likely the nuns tasked with copying down the music. Those signatures tell us a lot about how the music was created and credited, Feller-Simmons said.

“We tend to privilege composers, sidelining the invisible labor of historical performers and other musical actors. This music was made for the nuns, copied and performed by them in a female space,” he said.

Those convent performers would have had to navigate a whole different set of culture clashes than those in present-day Guatemala. Gender roles in Indigenous cultures don’t easily map onto the patriarchal attitudes of colonial Spain. Catholic authorities forbade nuns from playing “improper” instruments, like percussion or brass. Even those playing “acceptable” instruments were often not “acceptable” to see: Some convents had nuns perform behind the cloister for outside visitors.

To emphasize the context of the convent music, Newberry Consort director Malamut, who is also a trombonist, will have only female musicians play the Puebla pieces. But most of the program, like the Consort itself, is co-ed.

“If we’re really trying to get as close to reality as possible, I wouldn’t even be on the stage,” she said.

Deciphering these manuscripts, as Feller-Simmons has, takes time and patience. Besides the expected wear and tear, worms nibbled through some of the sheets. It was even more challenging to convert them into a performance-ready edition. The music doesn’t exist in a full score, with all the lines printed on the same page. Instead, only the individual parts survived — meaning researchers needed to round them all up to reconstruct how the works might have sounded. The notation style and clefs used in the manuscripts are also archaic.

“Some historical performers can probably read from the manuscripts, but it’s not the most comfortable thing,” Feller-Simmons said.

La instrumentación nunca se especifica en los manuscritos. | Cortesía Paul Gustav Feller-Simmons/Lilly Library, Indiana University Bloomington

As is typical for the time period, instrumentation is also never specified in the manuscripts. The Consort has made educated guesses about what instruments might have been at the musicians’ disposal and how they might have functioned in the ensemble. For that, Malamut scoured primary sources — correspondence, receipts, transatlantic cargo lists — for clues.

“We have a lot of plucked instruments: harp, guitars and sometimes even lute or theorbo could have been used,” she said. There is even evidence of a bajón, more or less an early version of the bassoon.

“The convents would have used those instruments to play the bottom of the range if they didn’t have a woman who could sing that low,” said Malamut.

How the Guatemalan manuscripts ended up in Bloomington, Indiana, reflects the fraught colonial history of the region. Catholic missionaries who returned to the Huehuetenango region’s parish in the 1960s were shown some old chests in its holdings. Inside were some 50 books of music, preserved and venerated by area parishioners like relics. Interspersed in the books’ pages were brief accounts of local history, noting visits from church dignitaries and documenting births and deaths.

Paul Gustav Feller-Simmons estudió y editó una serie de villancicos antiguos que se remontan a México y Guatemala de los siglos XVI y XVII. | Cortesía Paul Gustav Feller-Simmons

The books were taken for research, but most were sold off at auction to collectors. To date, only 19 of the 50 books survive and 17 of those ended up at Indiana University. Microfilm copies were made of some of the lost texts, but not all.

Traducido por Gisela Orozco para La Voz Chicago