If there’s a sport worth obsessing over, it’s basketball. What a beautiful game: shoes squeaking across shiny hardwood floors, the swish of the net when a perfect shot whips through, a contest that requires teamwork but celebrates individual style.

When I was a grammar school hooper, my dad gave me the 1995 book Hoop Dreams: A True Story of Hardship and Triumph by Reader columnist Ben Joravsky. The book is based on the 1994 documentary film Hoop Dreams, which follows two Chicago kids, Arthur Agee and William Gates, as they pursue professional basketball careers from eighth grade to freshman year of college.

On Saturday, November 9, Chicago Humanities will gather the two players and the filmmakers—Steve James, Peter Gilbert, and Frederick Marx—for a panel about the film. After 30 years, Hoop Dreams is still considered one of the greatest American documentaries, not only because of its cinematic storytelling but also its enduring relevance.

Hoop Dreams at 30

Sat 11/9, 5:30 PM, Logan Center for the Arts, University of Chicago, 915 E. 60th, $25 general admission, $20 CHF members (“Friends and above”), $10 students and teachers, free for CHF Humanist Circle members and above

chicagohumanities.org/events/attend/hoop-dreams-30th-anniversary

The film remains timely, in part, because of “the odds that William and Arthur and their families are trying to overcome,” James, the film’s director, told the Reader. “Namely, racism, besieged communities, and the circumscribed opportunities for Black families. This is, needless to say, an unfortunate way in which Hoop Dreams has remained relevant.”

When asked how reception to the film has evolved, James said he thinks it has remained about the same, but it’s now being shared across generations. “The difference is that I think families with sports-dreaming kids often recommend the film to them as something that resonated with them years ago. I like that aspect of Hoop Dreams’s legacy.”

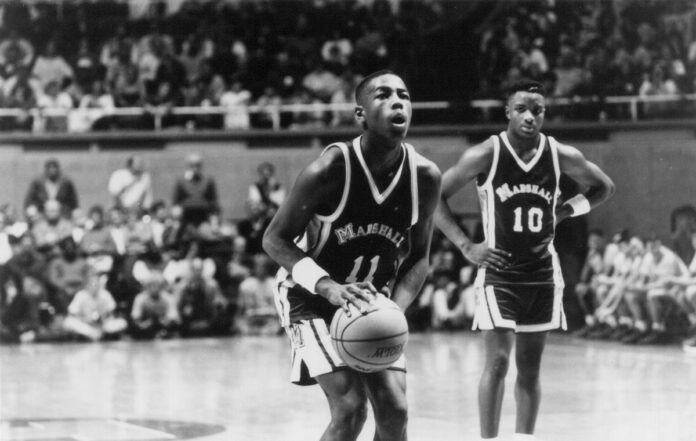

Credit: courtesy Kartemquin Films

When my dad gave me the book, it certainly seemed like the kind of story a basketball–obsessed kid like me would revel in. I played year-round, watched old Bulls VHS tapes to try to model my game after Scottie Pippen, and flicked the ball above my head in bed before falling asleep most nights. While Arthur and William’s love of the game mirrored mine in many ways, their story left me feeling deeply sad, making me rethink my own relationship to basketball. To me, it wasn’t an inspirational story about following one’s dreams; it was about two Black families living in a manufactured nightmare—one with systems designed to make some people fail.

When Arthur and William get into St. Joseph High School, a predominately white Catholic high school in the western suburb of Westchester that closed in 2021, it seems like the opportunity of a lifetime. After all, the likes of two-time NBA champion Isaiah Thomas was a St. Joe’s Charger. But a series of challenges emerge that seriously question the ethics of the school, its storied basketball program, and the basketball recruitment complex as a whole.

Arthur and William don’t come from means. Their partial scholarships to St. Joe’s give their families a sense of hope. But when Arthur’s parents lose their jobs, he’s forced to leave St. Joe’s because they can’t afford the tuition increase. Arthur transfers to John Marshall High School and continues playing ball, but the disruption to his education has lasting effects. He misses multiple weeks of classes at St. Joe’s because of the debt and loses a semester’s worth of credits after being out of school.

“If he was going out there and he was playing like they had predicted him to play, he wouldn’t be at Marshall,” says the school’s head basketball coach Luther Bedford in the film. “Economics wouldn’t have had anything to do with him not being at St. Joe’s. Somebody would have made some kind of arrangement, and the kid would’ve still been there.”

It’s hard to argue with Bedford’s explanation. William is seen as having more potential than Arthur on the basketball court. He’s often viewed as the next Isaiah Thomas. But when William’s family can’t afford tuition, a sponsor pays for him.

Hoop Dreams shows us the human cost of continuing to turn a blind eye to the American nightmare many are forced to endure.

Even though one of the boys is seen as a potentially more valuable player, he’s still let down by the system. After William blows out his knee, Gene Pingatore, St. Joe’s head basketball coach, leaves it up to William to decide when he returns—a choice some in the film believe was irresponsible to entrust to a 16-year-old. William rushes to play again and reinjures his knee, limiting his confidence, playing ability, and arguably his basketball prospects.

“I’m very disappointed . . . in the system. He shouldn’t have been out there playing,” says William’s brother-in-law, Alvin Bibbs, after William reinjures his knee. “If winning’s that important, we need to reevaluate the program.”

It’s no wonder William is eager to get back on the court. The dreams of both Arthur and William are, in fact, hoop dreams: the only way they and others feel they can succeed is to dribble a basketball. They live in a system that gives Black kids very few options—and sometimes no options at all. Hoop Dreams is a reflection of our past and current unwillingness to directly face the racism, exploitation, and inequalities that hurt kids in neighborhoods and education systems across the country. The film shines brightest when it alludes to these injustices, largely through its Black subjects.

Credit: courtesy Kartemquin Films

Later in the movie, the filmmakers insert a Spike Lee cameo during the Nike All-

American camp that William attends, in which Lee explains the investment-profit model present in many school basketball programs to the gathered kids.

“You have to realize that nobody cares about you,” says Lee. “You’re Black. You’re a young male. All you’re supposed to do is deal drugs and mug women. The only reason why you’re here—you can make their team win. If their team wins, these schools get a lot of money. This whole thing is revolving around money.”

At one point, Arthur’s mother, Sheila, tells the filmmakers how difficult it is to live on welfare month to month and make ends meet. Her husband has left after struggling with a drug addiction. The family went without lights and gas for three months, Sheila says, after she missed one welfare appointment. “So you know what the system is saying to me?” Sheila asks the filmmakers. “Do you know what it’s saying to a lot of women in my predicament? They don’t care.”

Perhaps one of the most disturbing aspects of the story is how often recruiters, coaches, and others at St. Joe’s fail to see the exploitative side of the sports industry. But ultimately the entire system is the real antagonist. As is the mirage of the American Dream. Hoop Dreams shows us the human cost of continuing to turn a blind eye to the American nightmare many are forced to endure.

Hoop Dreams (1994)

PG-13, 170 min. Max, Paramount+, streaming free on Philo, Pluto TV, Crackle

Throughout Hoop Dreams, several subjects seem to see through the veil at various points, including Arthur and William.

Perhaps William’s disillusion is most evident by the end of the film: “Four years ago, that’s all I used to dream about was playing in the NBA,” he says while sitting in his bedroom. “I don’t really dream about it like that anymore. Even though I love playing basketball, I want to do other things with my life too. If I had to stop playing basketball right now, I think I’d still be happy.”

When I first learned Arthur and William’s stories as a kid, my takeaway was similar to that final reflection: as amazing as basketball is, Black life, and Black dreams, are so much greater than hoops.