On July 14, 2018, Harith “Snoop” Augustus, a barber in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood, was shot to death by Officer Dillan Halley. Police had stopped Augustus after noticing that he had a gun under his shirt. As two officers attempted to detain him, Augustus—aware as any Black man might be in his situation of how such an incident might escalate—ran into the street, upon which Halley fired five shots, killing him on the spot. The police later claimed he had reached for his gun, a narrative that emerged as a classic example of the police’s interminable commitment to justifying their unlawful brutality.

Bill Morrison’s short film about Augustus’s death, Incident, is screening Monday, December 9, at the Gene Siskel Film Center. Morrison, who has watched the bodycam and surveillance footage of the incident, many, many times, tells me, “He wasn’t thinking about being stopped. He was scratching his back.”

Morrison will appear in person at the Film Center for a postscreening dialogue, joined by Jamie Kalven, founder of the Invisible Institute and the intrepid journalist whose reporting on the Laquan McDonald shooting brought that injustice to light and who also reported on Augustus’s shooting. (Morrison and Kalven are family friends, so the latter’s work was the inspiration for Incident.)

It’s difficult to reduce Morrison’s filmmaking, experimental as it is, down to a simple description—the appreciation and understanding of it are in the viewing. He’s largely worked with decaying celluloid (2002’s Decasia, 2016’s Dawson City: Frozen Time), breathing new life into these imperfect and previously believed to be lost images and creating new narratives in the process. Incident, which utilizes bodycam and surveillance footage of the shooting, isn’t so much a deviation as an evolution of how Morrison approaches archives and the images contained there. We spoke via Zoom about his film in advance of the Film Center screening.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kat Sachs: Your earlier works engage so much with the decay of physical film, whereas Incident deals with the overwhelming abundance of digital footage. How did this shift affect your creative approach to the themes that you wanted to explore?

Bill Morrison: Incident is still an archival piece; it still talks about the archive in a different way. . . . With decayed footage, it’s hard to get your hands on. It’s [because of] my privileged relationship with certain archives that I’ve been able to rescue it, and so in a way, it’s lost, or it certainly would be lost if I didn’t reproduce it and put it into my films, whereas this is a different kind of disappearance. These images are so common and so ubiquitous that they fall into an enormous archive that is not watched by virtue of the fact there’re just so many images like it. And if it gets rubber-stamped by the authorities as, “There’s nothing to look at here,” then we tend to not go back and examine it. It’s a different kind of obsolescence, I guess you’d say, and it also obviously speaks to a decay of society, quite literally.

This collection was remarkable because of the work Jamie Kalven did and the lawyers [did] on behalf of the family—they were able to get an extraordinary amount of footage from the city . . . body-worn cameras, surveillance cameras, closed-circuit TV, and dashboard cameras that told this story from many perspectives. When I saw how much coverage there was and that it could be synced to tell the story from different views, it resonated in different ways for me. Jamie and I are old family friends. I was aware of his work and had often asked about whatever project he was working on.

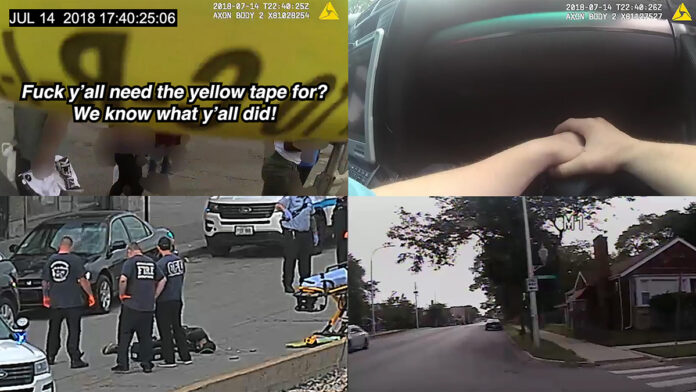

I had often said there is this idea of a Rashomon, where different stories reveal different realities based on who’s holding the camera or what kind of camera it is, and that those different types of media tell different types of story, which is sort of a compelling, 21st-century update of Rashomon [1950]. That remained a theoretical film idea we thought we might explore one day, and when this came up, [Kalven] wrote about it in the Intercept, and then more footage was released in 2022, and he wrote another article. At that point, most footage was uploaded to YouTube. I started downloading clips, seeing how they could fit together, and creating a structure of split screens or quad panels, always prioritizing this master shot, the eye-in-the-sky surveillance camera capturing the event, so we’d always be aware of the victim on the ground and everything happening around him. I saw the different points of view as a different way of telling a larger story, and that was very compelling to me.

With the Laquan McDonald case, the Feds eventually stepped in and said, “All this material has to be released in 60 days, you can’t hold onto it,” and so that also changed the nature of this type of footage, that officers were aware that this was all gonna become public, and therefore they started creating a narrative, which I also found compelling—that the presence of an archive dictated the action.

Incident (2023)

30 min. Mon 12/9, 6:15 PM, postscreening dialogue with director Bill Morrison and journalist and Invisible Institute founder Jamie Kalven, Gene Siskel Film Center, 164 N. State, $13 general admission, $8 youth and seniors, $6.50 Film Center members, $5 SAIC faculty and Art Institute staff, free for students

siskelfilmcenter.org/incident

What were the challenges of working with the bodycam footage, both technically and emotionally?

I wouldn’t say any officer was a trained cinematographer, and of course, kind of ridiculously, they’re asked to turn these cameras on at the beginning of an incident, so they have to make a judgment call, “Oh, now I’m in an incident,” just as [the] natural incident is occurring. That said, much of the footage didn’t begin where you’d want it to and often ended too soon. Officers turned it off—[it’s] a theme in the piece, where they say, “Don’t say nothing on that camera.” Eventually everyone turns their camera off because the poor officer who’s assigned to summarize it, to write the report on it, can’t get a straight answer from anybody until everyone’s camera is turned off.

My film explores the aftermath—what do they do with the corpse? How do the cops react? And a big part of that is, also, how does the crowd react? The crowd becomes a Greek chorus who are incredibly observant. One man even says, “You whisk them away so they can get their stories together,” which is exactly what’s happening.

In bringing all perspectives into the same frame, are you hoping this approach limits interpretive ambiguity, or do you welcome varied responses?

Well, I do welcome a range of responses. The New Yorker posted it on their YouTube channel, so there are comments allowed there, and if you go to those comments, there are quite a bit of people who find Snoop at fault. But, be that as it may, I’m presenting the footage, and that’s what’s important to me. I really wanted it to be about the 20 minutes that the cameras were on, and that we had that footage for, so that it becomes about: what does the footage show us?

To me, there’s not a shadow of a doubt that the police are culpable for at least manslaughter. But there are also rules that allow a gray area, always siding with police, saying it’s a dangerous job, that he was armed, and they couldn’t be sure.

It’s interesting how the police’s perspective often becomes the default “objective” point of view in these situations, even as you present the footage objectively and allow subjective responses.

That relates to how, in the archive, it’s rubber-stamped as, “This is how it went down.” Snoop’s fault is assumed, case closed. The very next night, they released a freeze-frame [on the news] where it appears Snoop is reaching for his gun. Because I’ve watched this a lot, I know that he’s already been shot at that time, but if you take that frame out of context and show it to the public and say, “This is the guy that the cop shot last night,” it’s immediately going to change public perception. He’s painted as a perpetrator, as a threat to society. The cop protected us all. That story was successfully spun. Harith Augustus’s name never entered the canon of repeatable names that the nation has sadly accrued.

“I think that you could watch this film 20 years from now and still understand it, not necessarily about these players, but about this country.”

You’ve mentioned how police behavior changes with footage, with officers performing on camera. How does this impact the narrative?

It’s interesting because what I think happens is that—and this could happen without a camera there, too—is that they start repeating the story to each other. Everyone’s saying, “OK, this is the official narrative,” you know? And so you see that happen immediately, with Halley saying, “Police shot.” And then he tells his sergeant that this guy pulled a gun on him.

We see that, actually, [another officer] takes Harith’s gun out of his holster, so there was no way that anybody pointed a gun at that officer. But that becomes the official narrative.

Do you think Officer Halley believes his version of what happened?

On some emotional level, he certainly does. By now he must, because he got off with a slap on the wrist. I understand from another officer that he’s sort of a hardened vet now, and that this was an early trial, and he faced it. This sergeant in the car with him says, “You shot him in the head.” He says, “I don’t know,” and she says, “Damn, that was a good shot.” He’s been lionized for this deadly murder.

The incident draws a parallel to the shooting of Laquan McDonald. What’s the significance of revisiting that case in the context of Augustus’s death?

My access to this collection was sort of also mandated by Laquan McDonald, and then of course, narratively, the city’s really in turmoil at that time, wondering how that case is gonna end up.

It goes to trial in September. Until that time, no cop had ever done any time for the murder of a Black man. So there’s a lot of anxiety, and I think that’s palpable, especially in [the South Shore] neighborhood. You hear a bunch of the crowd say, “You already killed one of ours. Now, you’ve killed another, you’re just starting to take random people out.” So the Laquan McDonald case is on everyone’s mind right then.

What’s the value of elevating this to cinema in relation to archives and assembling footage? What makes it cinema?

People ask me [if] I hope that this case will get reopened. That never was my intention. I do think that it narratively provides some closure for the family, in that now the world could see what happened to [Augustus’s mother’s] son. When we showed this film at the Chicago Humanities Festival, Snoop’s mom was there, and she stood up, and that’s what she said. She said, “We haven’t won any cases, but now everyone can see what happened.” And she turned to me and said, “It’s your job to tell this story to the world.” So I do feel, for her, there’s a sense of narrative justice in showing this film, but . . . this is no longer a current case. It’s six years old. But it’s an iconic story. It’s a story that tells, in incredible detail, the dynamics that are at stake in terms of why the officers are there and who called the officers there: their training and their background, their prejudice, and why Snoop is there, why he has a gun, the laws that allowed him to have a gun, the laws that made a Black man who’s carrying a gun a suspect, whereas a white man carrying a gun might not be. The yellow tape creates this zone around the corpse, whereas the corpse is being ignored. There are just a lot of elements of the story that tell the greater story of racism in this country, so I think that it distills that story in this sort of iconic way. And I recognized that and thought that this is about these people, it’s about this victim, but it’s also a greater story, and a story that can last. I think that you could watch this film 20 years from now and still understand it, not necessarily about these players, but about this country.

“Harith Augustus’s name never entered the canon of repeatable names that the nation has sadly accrued.”

A new collective bargaining agreement allows officers to turn off body cameras and delete postincident footage. How does this change affect documentaries holding power to account?

That’s immense, and I think we’re going to find that in this upcoming administration across the board. This is a sort of remarkable collection of footage in that I don’t think it exists anywhere that you would see this kind of coverage. This was a blitz, of coming after the city and them acquiescing, between Jamie and the lawyers for the family. I think Jamie’s stature and his history with the city, you know, they gave him what he asked for.

I think they were also relatively assured that no more damage was going to be done, and so, here it is, knock yourself out. I think [the agreement has] been ratified by the city, by the City Council, but it hasn’t passed Fed. We’ll have to see how that turns out. At this point, I’m not that hopeful that it’ll turn out better, but it is preposterous, the way it’s worded. It’s that if there’s any conversation about what just happened between two officers, then that footage becomes deletable, and you can invite any occasion to say, “Well, that was screwed up,” and “Whoops, you just talked about it. Now we can delete it.” So it really is a loophole that allows you to delete anything. If that passes, I don’t know what the possibility is of this footage effecting any changes. But then again, here we have just a plethora of footage, and it still didn’t effect any change. We still got the same outcome. You can have all the footage in the world, but whoever’s able to spin that image on the nightly news or withhold it or delete it are the people in control of the footage.

And that’s ultimately telling the story that we hear. I think that this film is somewhat alarming because it speaks to all the stories that we don’t hear and all the [incidents] where we can’t see this footage. And even if we could, we can’t do much about it.