Dick Allen, who died in 2020 at age 78, was elected Sunday to baseball’s Hall of Fame by the classic era committee. Here’s a column the Sun-Times’ Richard Roeper wrote about Allen in 1989:

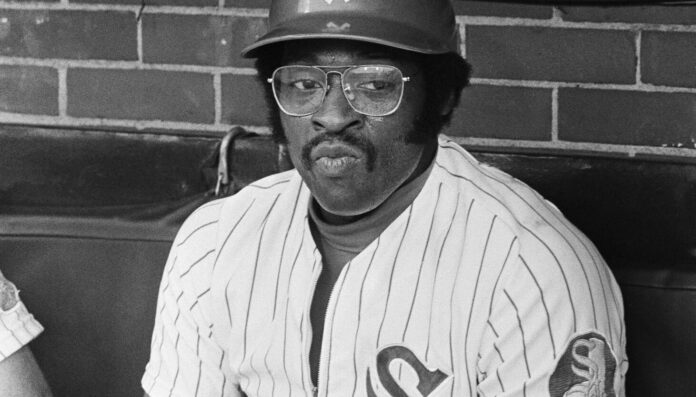

There was a routine he went through every time he stepped in the box — plant the feet, push the helmet down on the Afro, adjust the tinted glasses, tug at the left sleeve, then the right, grip the mammoth 40-ounce bat at its base and wave it back and forth in short bursts like a lethal weapon …

It was the summer of 1972, and Harry Caray was broadcasting the White Sox game from the center field bleachers in Comiskey Park. Dick Allen got hold of a fastball and hit a low line drive that never got more than 30 feet off the ground. Like a laser beam it zipped over the wall, over the bullpen, past the 440-foot sign, crashing into the bleachers. Harry Caray spilled beer all over himself trying to get out of the way.

After the game ended, my friend Shemp and I stayed a step ahead of the Andy Frains and managed to hide in the park until practically everyone had gone home. I hopped onto the field and circled the bases, while Shemp stood in the dugout and clapped his hands. After I crossed the plate, I stood and looked out at the spot where Dick Allen’s home run had landed. It was an impossibly long distance for a human being to hit a baseball. Of course, in the summer of 1972, Dick Allen wasn’t a human being, not on the baseball field. He was Superman.

Dick Allen sits at the bar in the Pump Room, quaffing bloody marys and toking on a miniature cigar. The sideburns are shorter than they were in ’72, but he still has the trademark glasses and mustache, still looks powerful.

He hasn’t been back to Chicago very often since 1974, his last season with the Sox. He’s here now to promote his autobiography, “Crash,” which details one of the most tumultuous, controversial careers in baseball history. I get the feeling that he wouldn’t be here if he didn’t have to be here.

“I never liked tape recorders,” he says when I set mine on the bar.

But he lets his guard down after I tell him about watching him do a patented decoy base-running move in which he would go from first to third on a passed ball or a wild pitch.

“All right, Rope,” Dick Allen says to me. “You know about that move, then you know the game.”

From that point on, Allen is forthright, almost effusive. He talks about 1963, when he was the first black minor league player in the state of Arkansas; about getting called up to “The Show” in Philadelphia; about drinking Heineken in the clubhouse between trips to the plate; about coming to Chicago in 1972 and almost singlehandedly leading the White Sox pennant drive, which fell just short. He talks about showing up late for games, difficulties with owners, domestic problems and he talks about Life After Baseball.

“I don’t want to coach or manage,” Allen says. “I can’t see putting on the uniform if you’re not going to play the game.”

He was the only athlete I ever tried to imitate. Like Dick Allen, I wore No. 15, I wore a helmet on the field, I wrote messages in the infield dirt, I wore two batting gloves, I learned to juggle three baseballs. I even used an oversized bat and tried to duplicate his swing, which is probably why I set a Sullivan League mark for most strikeouts in a single season.

“The problem with you,” one coach told me, “is that you imitate Dick Allen when you should be imitating Pete Rose.”

That coach was wrong. Allen may have had his misadventures off the field, but when he played, he went all out. He was a natural stylist, but he also was an intelligent student of the game. Just as a garage band guitarist gets more from the music when he cops a lick from Eric Clapton, I extracted more out of baseball because, even though the ability might have been lacking, I tried to play it with the style and attitude of Dick Allen.

Allen has to move on to an appointment with the mayor, but before leaving I tell him about an 11-year-old kid sitting in the center field bleachers and watching the frozen rope of a home run that nearly decapitated Harry Caray.

“You should have waved,” Dick Allen says. “I would have hit it to you.”