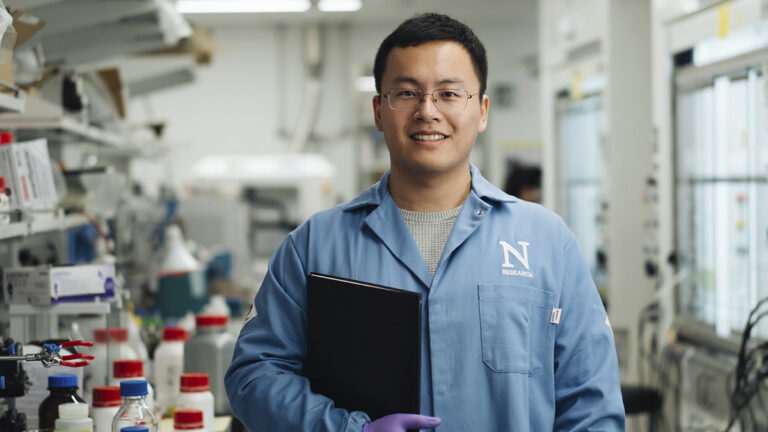

Bin Chen, 33, is a research associate professor in the chemistry department at Northwestern University, where he manages a team of 30 people within the 80-member lab led by Canadian scientist Ted Sargent. The team is developing materials used in renewable energy applications, with support from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Energy Technologies Office. Chen focuses on perovskite solar cells, a relatively new technology with great potential to increase efficiency and reduce costs. He’s also working on photodetectors using quantum dots and on field-effect transistors using two-dimensional materials, which will help computer processors run faster and use less energy.

I got my PhD in material science, but I was studying in a place that has an abundance of sunlight, in Arizona. My lab at that time was on the second floor, and I needed to go through the first floor, which [was] the solar research center.

My girlfriend was studying at the University of Toronto, and I wanted to get a job in Toronto, so we [could] end the two-body problem. [Laughs.] Fortunately, there was a very big research group led by professor Ted Sargent at the University of Toronto, hiring a postdoc to work on perovskite-based solar cells. I clearly remember that was April 18 of 2018. So I applied, and then I got admitted, and that’s how I started my solar work.

In 2022, Ted got an offer from Northwestern, and he asked me if I would like to move with him. This was a good opportunity to get into the U.S. system. The U.S. has maybe the best renewable research laboratory, supported by DOE (Department of Energy). That’s the NREL—National Renewable Energy Laboratory. I think that might be the best energy research lab in the whole world.

When we were in the University of Toronto, it was basically just us working on solar cells and perovskites. But there are great people [at Northwestern]: professor Mercouri Kanatzidis, professor Mike Wasielewski, and a few others. So we felt that Northwestern has a really, really good platform for us to achieve our vision.

[Renewable energy] is important because it affects our future generations. It’s about sustainable development. What I mean specifically is global warming and the CO2 in the atmosphere that keeps driving up the temperature.

You have to actually use renewable energy, so that you reduce the generation of carbon dioxide. That’s the viable way to reduce global warming.

People like to talk about net zero—meaning that if you generate a certain amount of CO2, then you have to capture a certain amount of CO2. It’s not likely to happen if you just keep using nonrenewable energy—like, you’re still burning coal, and then at the same time you’re trying to remove the carbon from the atmosphere. You have to actually use renewable energy, so that you reduce the generation of carbon dioxide. That’s the viable way to reduce global warming.

Solar is going to play a big part. The IEA (International Energy Agency) is doing the road mapping of how we should build a more sustainable future using different energy sources. In 2050 the total generation of electricity will consist of a large portion from solar energy. I think it’s more than 30 percent. [Editor’s note: According to energy think tank Ember, solar’s share of global electricity generation was 5.5 percent in 2023.]

How perovskite was able to scale up in terms of efficiency over the past 15 years is incredible. It improved from below 10 percent power conversion efficiency to more than 26 percent in less than ten years. The same kind of improvements took silicon more than 40 years.

To make silicon [solar cells], you have to purify the silicon at really high temperatures, like 800 Celsius. It’s very expensive, and it is generating a lot of carbon dioxide. But for perovskites, it doesn’t need to go through all this high-temperature processing. You can just make an ink of perovskite solution, and then you can cast it on a substrate or print it, like printing a newspaper—at low temperature, like 100 Celsius. So the energy cost is very low, and the material cost is also low.

Perovskite is a very, very good light absorber. It is much better than silicon. Silicon needs, like, 100-micron thickness in a solar cell, because it doesn’t absorb light very efficiently. But for perovskite, you just need one micron. So it’s like 100 times reduction in the thickness. You can make really, really lightweight perovskite solar cells, and because of the reduction of thickness, you can make it flexible. You could use perovskite on drones or on top of your cars without adding too much weight.

Silicon has a very defined bandgap, meaning it absorbs only a certain fixed amount of the solar spectrum. But perovskite is very adjustable—there are many, many perovskites available, because it’s a name just to describe certain arrangements of atoms in the crystal structure. So you can change the perovskite’s chemistry. You can make it absorb the blue light, you can make it absorb the green light, you can make it absorb the red light or infrared light. That opens up the opportunity for you to combine these different light-absorbing perovskites to make what we call multijunction solar cells—instead of having just one layer of materials, you now have two or three materials absorbing different portions of the sunlight.

Silicon needs, like, 100-micron thickness in a solar cell, because it doesn’t absorb light very efficiently. But for perovskite, you just need one micron.

Perovskites and silicon make the perfect pair in terms of the color of light that they absorb. Silicon solar is such well-developed technology, so people want to keep the momentum going—if you can do very little by integrating perovskite into silicon technology, then you do it. It doesn’t add too much cost, and then you get all these benefits of multijunction solar cells with higher efficiency.

Perovskites just all of a sudden opened up that possibility. In the past, people have been working on multijunction solar cells, but these are based on so-called III-V semiconductors. They’re so expensive that they are only used in basically two scenarios: outer space exploration and military.

The main challenge is the reliability of those perovskite solar cells. We have seen really significant progress in the past few years—it’s about finding the root cause of degradation mechanisms and a solution for that. We have been collectively as a community improving the device operational lifetime of perovskite from less than ten hours to now more than 2,000 hours.

There is no standard in the industry that is based on perovskite, because it’s so new. So I think if perovskite panels can pass the standard testing for silicon panels, then they will be most likely accepted by consumers, right? We have made big progress on that as well.

You’re testing the solar cells in very humid and high-temperature conditions. You are cycling between -40 Celsius to 85 Celsius. You are doing some hail tests, like throwing things on the panel to see if it breaks. It’s basically stress testing.

When we are calculating LCOE (levelized cost of electricity), it’s calculating the cost of the lifetime energy generation. So comparing to silicon, we have higher efficiency using perovskites—maybe it lasts shorter, but the amount of energy generated over the shorter lifetime can be equal to the energy generated by silicon over a longer lifetime. So in that case, you’ll be OK. And that’s definitely true. That’s a way to get the product to the market sooner.

How much of a concern is it to have lead in the perovskites? There is a calculation for EU regulations called RoHS (Restriction of Hazardous Substances), and it basically calculates how much of a hazardous material you can have in a commercial product, based on weight. Most of the weight comes through the glass and other things, and lead is just a tiny amount—below the threshold. There is lead in silicon panels as well, in the interconnections, soldering things.

If you’re talking about using perovskite-based consumer electronics, your cell phones or computers, that might be a problem—you’re using them every day. But for solar panels outside, it’s most likely OK.

People have been trying to find alternative metals to lead to develop high-efficiency perovskite solar cells. But so far, it’s not very successful. And lead-free compounds face serious stability issues. Most of those lead-free perovskites are based on tin, and those tin compounds really, really like to be oxidized. So that’s the structure breakdown, and you don’t have perovskite anymore. And also the cell fails.

In the broader picture, we need to reduce carbon emissions. It’s not just solar that needs to be there. Other sources of renewable energy will make big contributions—like wind, onshore and offshore. Wind and solar together will account for more than 50 or 60 percent. Then there are some others, like nuclear.

These are just generation, right? And a lot of those technologies, including the two big ones, wind and solar, they are nondispatchable. That means at night or when there’s no wind, you cannot generate any electricity. So that’s a problem. We need to have better storage options—maybe batteries, maybe other forms of chemical storage.

I do consider myself very concerned for the future. What I’d like to see happen, first of all, is the adoption of renewable energy. We cut the use of coal, fossil fuels, so that we don’t keep the temperature going higher and higher. And then we don’t see those icebergs melting and the seas going above some of those island nations, so they have nowhere to live. That’s what I have in mind when I talk about renewable energy.

This was originally published in the 2024 edition of our People Issue, the Reader’s annual special of first-person stories, as told by your neighbors, classmates, and the weirdo at the end of the bar.